Western pattern diet

The Western pattern diet is a modern dietary pattern that is generally characterized by high intakes of pre-packaged foods, refined grains, red meat, processed meat, high-sugar drinks, candy and sweets, fried foods, industrially produced animal products, butter and other high-fat dairy products, eggs, potatoes, corn (and high-fructose corn syrup), and low intakes of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, pasture-raised animal products, fish, nuts, and seeds.[2]

Dietary pattern analysis focuses on overall diets (such as the Mediterranean diet) rather than individual foods or nutrients.[3] Compared to the "prudent pattern diet", which has higher proportions of "fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and poultry", the Western pattern diet is associated with higher risks of cardiovascular disease and obesity.[4]

Elements

[edit]

This diet is "rich in red meat, dairy products, processed and artificially sweetened foods, and salt, with minimal intake of fruits, vegetables, fish, legumes, and whole grains."[5] Various foods and food processing procedures that had been introduced during the Neolithic and Industrial Periods had fundamentally altered 7 nutritional characteristics of ancestral hominin diets: glycemic load, fatty acid composition, macronutrient composition, micronutrient density, acid-base balance, sodium-potassium ratio, and fiber content.[6]

In 2006 the typical American diet was about 2,200 kilocalories (9,200 kJ) per day, with 50% of calories from carbohydrates, 15% protein, and 35% fat.[7] These macronutrient intakes fall within the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDR) for adults identified by the Food and Nutrition Board of the United States Institute of Medicine as "associated with reduced risk of chronic diseases while providing adequate intakes of essential nutrients," which are 45–65% carbohydrate, 10–35% protein, and 20–35% fat as a percentage of total energy.[8] However, the nutritional quality of the specific foods comprising those macronutrients is often poor, as with the "Western" pattern discussed above. Complex carbohydrates such as starch are believed to be more healthy than sugar, which is frequently consumed in the standard American diet.[9][10]

The energy-density of a typical Western pattern diet has continuously increased over time. USDA research conducted in the mid 2010s suggests that the average intake of American adults is at least 2,390 kcal (10,000 kJ)[11] per day. Researchers that used different data collection/analysis methods have predicted that the average was about 3,680 kcal (15,400 kJ) per day.[12] By contrast, a healthy daily intake is much lower. Since American adults usually have sedentary lifestyles guidelines suggest 1,600–2,000 kcal (6,700–8,400 kJ) is appropriate for most women and 2,000–2,600 kcal (8,400–10,900 kJ) is appropriate for men with the same physical activity level.

A review of eating habits in the United States in 2004 found that about 75% of restaurant meals were from fast-food restaurants. Nearly half of the meals ordered from a menu were hamburgers, French fries, or poultry — and about one third of orders included a soft drink.[13] From 1970 to 2008, the per capita consumption of calories increased by nearly 25% in the United States and about 10% of all calories were from high-fructose corn syrup.[14]

Americans consume more than 13% of their daily calories in the form of added sugars. Beverages such as flavored water, soft drinks, and sweetened caffeinated beverages make up 47% of these added sugars.[15]

Americans ages 1 and above consume significantly more added sugars, oils, saturated fats, and sodium than recommended in the dietary guidelines outlined by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 89% of Americans consume more sodium than recommended. Additionally, excessive consumption of oils, saturated fats, and added sugars is seen in 72%, 71%, and 70% of the American population, respectively.[16]

Consumers began turning to margarine due to concerns over the high levels of saturated fats found in butter. By 1958, margarine had become more commonly consumed than butter, with the average American consuming 8.9 pounds (4 kg) of margarine per year.[17] Margarine is produced by refining vegetable oils, a process that introduces trans elaidic acid not found naturally in food.[18] The consumption of trans fatty acids such as trans elaidic acid has been linked to cardiovascular disease.[19] By 2005, margarine consumption had fallen below butter consumption due to the risks associated with trans fat intake.[17]

Vegetable consumption is low among Americans, with only 13% of the population consuming the recommended amounts. Boys ages 9 to 13 and girls ages 14 to 18 consume the lowest amounts of vegetables relative to the general population. Potatoes and tomatoes, which are key components of many meals, account for 39% of the vegetables consumed by Americans. 60% of vegetables are consumed individually, 30% are included as part of a dish, and 10% are found in sauces.[20]

Whole grains should consist of over half of total grain consumption, and refined grains should not exceed half of total grain consumption. However, 85.3% of the cereals eaten by Americans are produced with refined grains, where the germ and bran are removed.[21] Grain refining increases shelf life and softens breads and pastries; however, the process of refining decreases its nutritional quality.[22]

Environmental impact

[edit]The transition into a more westernised diet has several implications, particularly regarding the exportation of foods. As populations become more affluent, reflected in a growing GDP, they have more disposable income to purchase food from other countries, which facilitates this dietary transition. This has been observed in many developing nations. In low and middle income countries, this transition is rapid, and this is observed in countries such as Brazil, India, and South Africa. Westernised diets contribute to increasing greenhouse gas emissions. This occurs due to the large global supply chains that food production is a part of. Large areas in Latin America and South-East Asia dedicate a large proportion of their land towards agriculture and forestry, which then gets exported to other countries. This growing use of exports is driving greenhouse gas emissions.[citation needed]

Changing global diets also increase emissions. Increasing per capita incomes leads to urbanisation of a population. When this occurs, populations substitute a low-calorie and vegetable intense diet for more energy-intensive products that are characterised by increase in meat and refined fats, oils and sugar consumption. Once a nation reaches a certain point in development, diet can become the main driver for emissions, particularly when it is focused on a westernised diet.[23]

Health concerns

[edit]Based on preliminary epidemiological studies, compared to a healthy diet, the Western pattern diet is positively correlated with an elevated incidence of obesity,[4] death from heart disease, cancer (especially colon cancer),[24] and other "Western pattern diet"-related diseases.[9][25] It increases the risk of metabolic syndrome and may have a negative impact on cardio-metabolic health.[26]

Crohn's disease

[edit]A Western pattern diet has been associated with Crohn's disease.[27] Crohn's disease has its effects on the symbiotic bacteria within the human gut that show a positive correlation with a Western pattern diet.[27] Symptoms can range from abdominal pain to diarrhea and fever.[27]

Obesity

[edit]

A Western pattern diet is associated with an increased risk of obesity.[28] There is a positive correlation between a Western pattern diet and several plasma biomarkers that may be mediators of obesity, such as HDL cholesterol, high levels of fasting insulin, and leptin.[28] Meta-analyses have also shown that, compared to a healthy diet, a Western pattern diet is linked to increased weight gain among females[29] and adolescents.[30]

Diabetes

[edit]Several studies have shown that there is a positive correlation between adoption of a Western pattern diet and incidence of type 2 diabetes among both men[28] and women.[31]

Cancer

[edit]The Western pattern diet has been generally linked to increased risk for colorectal cancer.[32] Meta-analyses have found that diet patterns consistent with those of the Western pattern diet are positively correlated with risk for prostate cancer.[33][34] Greater adherence to a Western pattern diet was also found to increase the overall risk of mortality due to cancer.[35]

No significant relation has been established between the Western pattern diet and breast cancer.[36][37]

Prevalence

[edit]In recent years, diets in developing countries such as Mexico, South Africa, and India have transitioned to adopt more elements of the western-style diet. Overall dietary consumption in these regions now reflects a higher balance of processed sugars and fats over lower-calorie food groups like vegetables and starches.[38] In accordance with this pattern, the western-versus-eastern dichotomy has become less relevant as such a diet is no longer "foreign" to any global region (just as traditional East Asian cuisine is no longer "foreign" to the west), but the term is still a well-understood shorthand in medical literature, regardless of where the diet is found. Other dietary patterns described in the medical research include "drinker" and "meat-eater" patterns.[24] Because of the variability in diets, individuals are usually classified not as simply "following" or "not following" a given diet, but instead by ranking them according to how closely their diets line up with each pattern in turn. The researchers then compare the outcomes between the group that most closely follows a given pattern to the group that least closely follows a given pattern.

History

[edit]

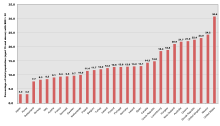

Other area (Yr 2010)[41] * Africa, sub-Sahara - 2170 kcal/capita/day * N.E. and N. Africa - 3120 kcal/capita/day * South Asia - 2450 kcal/capita/day * East Asia - 3040 kcal/capita/day * Latin America / Caribbean - 2950 kcal/capita/day * Developed countries - 3470 kcal/capita/day

The Western diet present in today's world is a consequence of the Neolithic Revolution and Industrial Revolutions.[42] The Neolithic Revolution introduced the staple foods of the western diet, including domesticated meats, sugar, alcohol, salt, cereal grains, and dairy products.[42][43] The modern Western diet emerged after the Industrial Revolution, which introduced new methods of food processing including the addition of cereals, refined sugars, and refined vegetable oils to the Western diet, and also increased the fat content of domesticated meats. More recently, food processors began replacing sugar with high-fructose corn syrup.[42]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Carrera-Bastos, Pedro; Fontes; O'Keefe; Lindeberg; Cordain (March 2011). "The western diet and lifestyle and diseases of civilization". Research Reports in Clinical Cardiology: 15. doi:10.2147/RRCC.S16919.

- ^ Halton, Thomas L; Willett, Walter C; Liu, Simin; Manson, JoAnn E; Stampfer, Meir J; Hu, Frank B (2006). "Potato and french fry consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 83 (2): 284–90. doi:10.1093/ajcn/83.2.284. PMID 16469985.

- ^ Hu, Frank B (February 2002). "Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology". Curr Opin Lipidol. 13 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1097/00041433-200202000-00002. PMID 11790957. S2CID 6369375.

- ^ a b Fung, Teresa T; Rimm, Eric B; Spiegelman, Donna; Rifai, Nader; Tofler, Geoffrey H; Willett, Walter C; Hu, Frank B (2001-01-01). "Association between dietary patterns and plasma biomarkers of obesity and cardiovascular disease risk". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 73 (1): 61–7. doi:10.1093/ajcn/73.1.61. PMID 11124751.

- ^ Bloomfield, HE; Kane, R; Koeller, E; Greer, N; MacDonald, R; Wilt, T (November 2015). "Benefits and Harms of the Mediterranean Diet Compared to Other Diets" (PDF). VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. PMID 27559560.

- ^ Cordain, L; Eaton, SB; Sebastian, A; Mann, N; Lindeberg, S; Watkins, BA; O'Keefe, JH; Brand-Miller, J (February 2005). "Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 81 (2): 341–54. doi:10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341. PMID 15699220.

- ^ Last, Allen R.; Wilson, Stephen A. (2006). "Low-Carbohydrate Diets". American Family Physician. 73 (11): 1942–8. PMID 16770923.

- ^ Food and Nutrition Board. Institute of Medicine (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 14–15. doi:10.17226/10490. ISBN 978-0-309-08525-0. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ a b Gary Taubes, Is Sugar Toxic?, The New York Times, April 13, 2011

- ^ Murtagh-Mark, Carol M.; Reiser, Karen M.; Harris, Robert; McDonald, Roger B. (1995). "Source of Dietary Carbohydrate Affects Life Span of Fischer 344 Rats Independent of Caloric Restriction". The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 50A (3): B148–54. doi:10.1093/gerona/50A.3.B148. PMID 7743394.

- ^ Bentley, Jeanine (January 2017). "U.S. Trends in Food Availability and a Dietary Assessment of Loss-Adjusted Food Availability, 1970-2014" (PDF). USDA.

- ^ Gould, Skye. "6 charts that show how much more Americans eat than they used to". Business Insider. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ^ Lobb, Annelena (September 17, 2005). "Eating Habits -- A Look At the Average U.S. Diet". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Philpott, Tom (April 5, 2011). "The American diet in one chart, with lots of fats and sugars". Industrial Agriculture. Grist. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ "A Closer Look at Current Intakes and Recommended Shifts - 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines - health.gov". health.gov. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ "Current Eating Patterns in the United States - 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines - health.gov". health.gov. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ a b "USDA ERS - Butter and Margarine Availability Over the Last Century". www.ers.usda.gov. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Cordain, Loren; Eaton, S. Boyd; Sebastian, Anthony; Mann, Neil; Lindeberg, Staffan; Watkins, Bruce A.; O'Keefe, James H.; Brand-Miller, Janette (February 2005). "Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 81 (2): 341–354. doi:10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341. PMID 15699220.

- ^ Iqbal, Mohammad Perwaiz (2014). "Trans fatty acids – A risk factor for cardiovascular disease". Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 30 (1): 194–7. doi:10.12669/pjms.301.4525. PMC 3955571. PMID 24639860.

- ^ "A Closer Look at Current Intakes and Recommended Shifts - 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines - health.gov". health.gov. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ "A Closer Look at Current Intakes and Recommended Shifts - 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines - health.gov". health.gov. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ "Whole Grains". The Nutrition Source. 2014-01-24. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), ed. (2023-08-17), "Emissions Trends and Drivers", Climate Change 2022 - Mitigation of Climate Change (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 215–294, doi:10.1017/9781009157926.004, ISBN 978-1-009-15792-6, retrieved 2023-11-22

- ^ a b Kesse, E; Clavel-Chapelon, F; Boutron-Ruault, M. (2006). "Dietary Patterns and Risk of Colorectal Tumors: A Cohort of French Women of the National Education System (E3N)". American Journal of Epidemiology. 164 (11): 1085–93. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj324. PMC 2175071. PMID 16990408.

- ^ Heidemann, C.; Schulze, M. B.; Franco, O. H.; Van Dam, R. M.; Mantzoros, C. S.; Hu, F. B. (2008). "Dietary Patterns and Risk of Mortality from Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and All Causes in a Prospective Cohort of Women". Circulation. 118 (3): 230–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.771881. PMC 2748772. PMID 18574045.

- ^ Drake, I; Sonestedt, E; Ericson, U; Wallström, P; Orho-Melander, M (May 2018). "A Western dietary pattern is prospectively associated with cardio-metabolic traits and incidence of the metabolic syndrome". The British Journal of Nutrition. 119 (10): 1168–76. doi:10.1017/S000711451800079X. PMID 29759108.

- ^ a b c Baumgart, Daniel C; Sandborn, William J (2012). "Crohn's disease". The Lancet. 380 (9853): 1590–1605. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60026-9. PMID 22914295. S2CID 18672997.

- ^ a b c Kant, Ashima K. (2004). "Dietary patterns and health outcomes". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 104 (4): 615–635. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2004.01.010. PMID 15054348.

- ^ Drewnowski, Adam (2007-01-01). "The Real Contribution of Added Sugars and Fats to Obesity". Epidemiologic Reviews. 29 (1): 160–171. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxm011. PMID 17591599.

- ^ Yang, Wai Yew; Williams, Lauren T; Collins, Clare; Swee, Chee Winnie Siew (2012). "The relationship between dietary patterns and overweight and obesity in children of Asian developing countries: A Systematic Review". JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 10 (58): 4568–99. doi:10.11124/jbisrir-2012-407. PMID 27820524. S2CID 21654985.

- ^ Hu, Frank B. (2011-06-01). "Globalization of Diabetes: The role of diet, lifestyle, and genes". Diabetes Care. 34 (6): 1249–57. doi:10.2337/dc11-0442. PMC 3114340. PMID 21617109.

- ^ Fung, Teresa; Hu, Frank B.; Fuchs, Charles; Giovannucci, Edward; Hunter, David J.; Stampfer, Meir J.; Colditz, Graham A.; Willett, Walter C. (2003-02-10). "Major Dietary Patterns and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Women". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (3): 309–14. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.3.309. PMID 12578511.

- ^ Fabiani, Roberto; Minelli, Liliana; Bertarelli, Gaia; Bacci, Silvia (2016-10-12). "A Western Dietary Pattern Increases Prostate Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Nutrients. 8 (10): 626. doi:10.3390/nu8100626. PMC 5084014. PMID 27754328.

- ^ Jalilpiran, Y; Dianatinasab, M; Zeighami, S; Bahmanpour, S; Ghiasvand, R; Mohajeri, SAR; Faghih, S (August–September 2018). "Western Dietary Pattern, But not Mediterranean Dietary Pattern, Increases the Risk of Prostate Cancer". Nutrition and Cancer. 70 (6): 851–859. doi:10.1080/01635581.2018.1490779. PMID 30235016. S2CID 52308508.

- ^ Entwistle MR, Schweizer D, Cisneros R (November 2021). "Dietary patterns related to total mortality and cancer mortality in the United States". Cancer Causes Control. 32 (11): 1279–1288. doi:10.1007/s10552-021-01478-2. PMC 8492557. PMID 34382130.

- ^ Sánchez-Zamorano, Luisa María; Flores-Luna, Lourdes; Angeles-Llerenas, Angélica; Ortega-Olvera, Carolina; Lazcano-Ponce, Eduardo; Romieu, Isabelle; Mainero-Ratchelous, Fernando; Torres-Mejía, Gabriela (August 2016). "The Western dietary pattern is associated with increased serum concentrations of free estradiol in postmenopausal women: implications for breast cancer prevention". Nutrition Research. 36 (8): 845–854. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2016.04.008. PMID 27440539.

- ^ Brennan, S. F.; Cantwell, M. M.; Cardwell, C. R.; Velentzis, L. S.; Woodside, J. V. (10 March 2010). "Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 91 (5): 1294–1302. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28796. PMID 20219961.

- ^ Dhakal, S.; Minx, J.C.; Toth, F.L.; Abdel-Aziz, A.; et al. "Chapter 2: Emissions Trends and Drivers" (PDF). Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. p. 254. doi:10.1017/9781009157926.004.

- ^ FAO FAOSTAT

- ^ These are supplied energy, intake energy are about 60-80% of supply. FAO estimates food supply of 2700 kcal to be satisfactory.

- ^ FAO Food Security

- ^ a b c Cordain, Loren; Eaton, S. Boyd; Sebastian, Anthony; Mann, Neil; Lindeberg, Staffan; Watkins, Bruce A.; O'Keefe, James H.; Brand-Miller, Janette (2005-02-01). "Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 81 (2): 341–354. doi:10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341. PMID 15699220.

- ^ Carrera-Bastos, Pedro; Fontes; O'Keefe; Lindeberg; Cordain (2011-03-09). "The western diet and lifestyle and diseases of civilization". Research Reports in Clinical Cardiology. 2: 15. doi:10.2147/rrcc.s16919.

Further reading

[edit]- Levenstein, Harvey A. (1988). Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504365-0. JSTOR jj.8501376. OCLC 16464971. About the changes in dietary advice and eating patterns between 1880 and 1930.